One of the best ways to prepare for a trip abroad is to learn a bit about the art. This can turn a dull visit to a museum into an exciting, even overwhelming experience. The world of Renaissance art may be intimidating for some, but the next time you visit a museum or see the art of the Renaissance in Italy, you might find these tips for interpreting Renaissance paintings helpful.

Tips to Understanding Renaissance Art

1) Look for the use of line

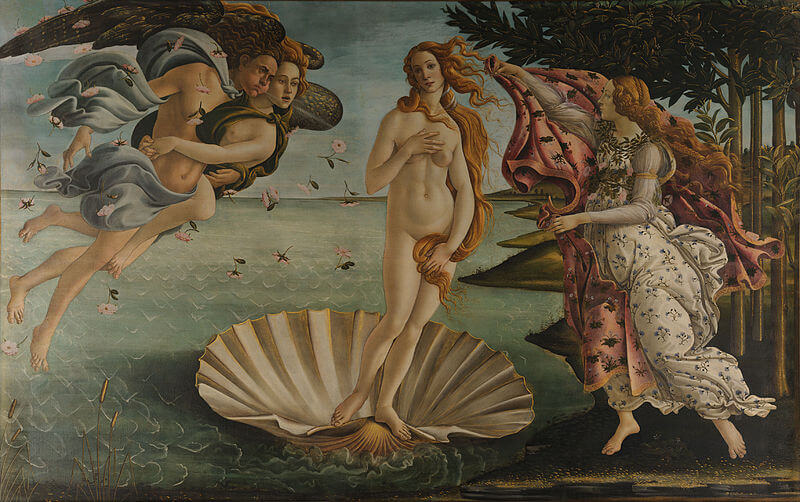

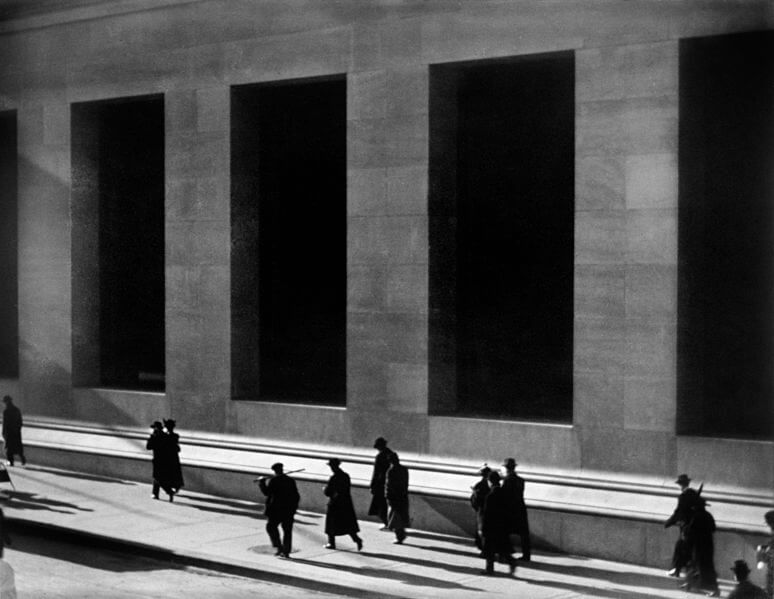

Linear perspective was created during the early Renaissance in the first part of the 15th century. It was one way of making paintings look more realistic by allowing artists to depict realistic, three-dimensional space. After that, artists like Botticelli showed off their command of perspective by using lines that converge in the background.

Another way artists showed perspective was by depicting architectural details that recede into space.

2) Realism was front and center

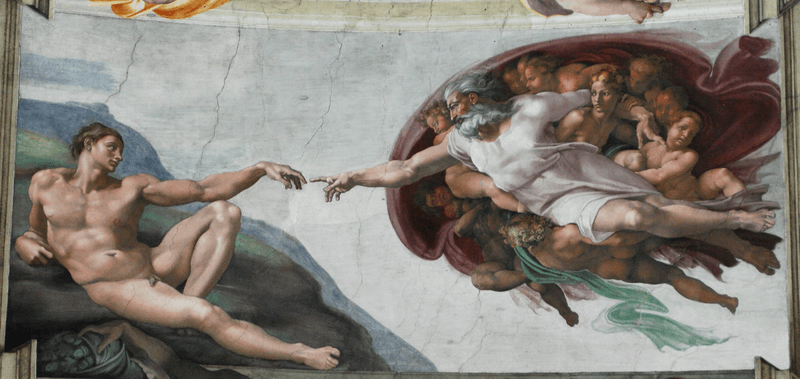

The main goal of the Renaissance was to reawaken an appreciation for man. Humanism took many forms, one of which was a celebration of the potential of humans, including the human body. Realistic representations of the human form became increasingly important, easily seen in Michelangelo’s work:

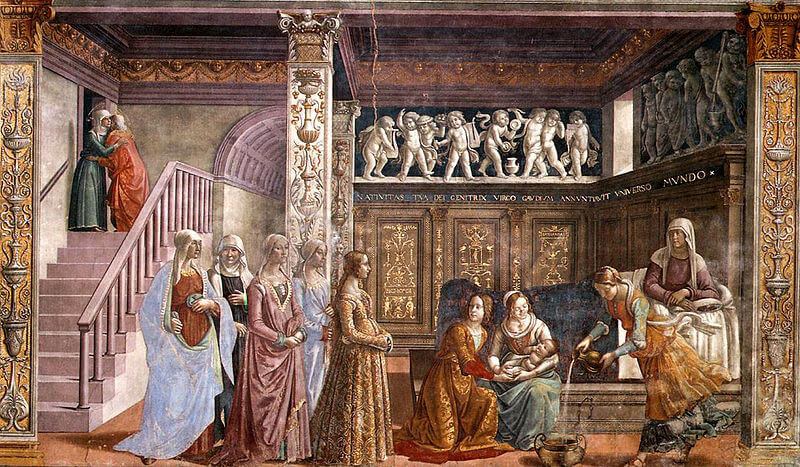

For many artists, realism also meant depicting the familiar: clothing, decorations, and landscape typical of 15th century Florence, not from 1400+ years earlier when these religious scenes actually took place. This means that you can get a feeling for what Renaissance Florence looked like through the little details in the paintings.

The fresco below provides a glimpse of the decoration, furniture, and clothing that were valued by the rich in Florence in the 15th century even though the painting depicts a completely different time period, the birth of the Virgin Mary.

Another way of introducing realism and the familiar into Renaissance art was to include familiar landscapes. This Biblical scene takes place with a landscape based on the Dolomite mountains of Northern Italy.

3) Who’s in the painting?

Pay attention to the faces you see in the painting. Do they all look the same, or did the artist depict people realistically, with unique features? Many paintings include self-portraits of the artist (usually the one looking out at the viewer instead of at the scene). This one is a self-portrait of the painter Ghirlandaio included among the many people in the painting.

It was also common to include the patrons in the painting. While the patrons may not be the most interesting people for you to think about, they were essential because they gave the artists work — commissions usually of religious scenes in an effort to secure a place in heaven. This was very common in Renaissance art.

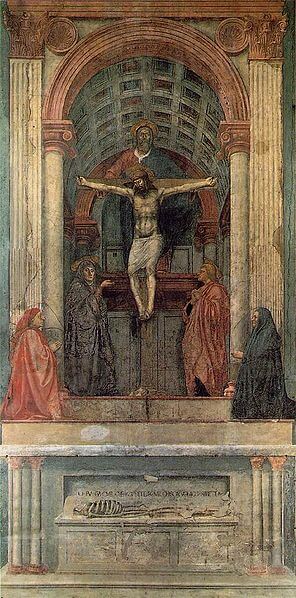

This early Renaissance fresco from the church of Santa Maria Novella shows the patrons kneeling at the bottom, one on either side of the scene.

A more interesting who’s who is the artist’s favorite model. In the case of Filippo Lippi, the young and beautiful Lucrezia Buti became his favorite model. Despite the fact that he was a monk and she was a nun, they had a 30-year love affair; in fact, their son Filippino Lippi became an artist of the High Renaissance.

4) Fine details

As Renaissance art progressed, artists became more adept at painting small details, such as the jewelry and headdresses that were fashionable at that time (see the above example as well). This gives you an opportunity to see what was considered beautiful, including hairstyles, accessories, and clothing, during the Renaissance.

Such attention to fine detail and an almost ethereal quality led to the delicate beauty in Da Vinci and Raphael’s paintings of the High Renaissance.

5) Allusions to the Roman and Greek past

Humanism meant a strong connection to the philosophy and arts of ancient Greece and Rome. The Italian Renaissance aimed to resurrect these, as we can see not only in the style of the the architecture but also in the stories portrayed in painting.

While religious themes were the most common subjects of the Renaissance, themes from ancient Greek and Rome, including mythology, became more popular with the support of Lorenzo de’ Medici in the late 15th century.

If you’d like to learn more about Renaissance art, visit these blog posts about art in Italy:

More on art and life in Italy:

Great distillation of a complex subject, Jenna. Thanks for the tour, and reminder of many revelatory art moments of my life. I’m especially glad you included Ghirlandaio; I did a paper on that fresco. It was an incredible thrill to see it in person and a pleasure to see it again here!

I love that fresco series, too. I saw it again last November, and it seemed quite different from how I remembered it. Funny how the memory works.

What a wonderful roundup of helpful tips to examining the works of the Renaissance! What a glorious time in art history and so happy to see so many faves of mine in this post, especially Masaccio, Botticelli and the master Michelangelo!!

Wonderful tips on understanding the Renaissance time period in art! I had never focused on the fact that the familiar was introduced through the clothing and the landscape – that’s the kind of information that I like to be able to point out to my daughter when we are viewing paintings.

Oh yes, I agree about pointing something like that out to kids. Makes it so much more interesting–and like a scavenger hunt as they try to find those details in more than one painting.

Great overview Jenna! These are excellent starting points. An aspect of Renaissance art I am always suprised and delighted by is how there is *always* more to a painting than immediately meets the eye. These images are so deeply ingrained in Western visual culture, it is easy to look at them and miss many wonderful little details that are in fact unusual or not what we may have originally thought.

A neat example of this is in the image types depicting the meeting of Christ and Saint John as infants. These types of works are very commonly seen, but are actually not from a biblical source – but instead a later account of the “Return to Egypt”, which became popular during the middle ages. For artists however, the story and image type was a welcome opportunity to depict images of the Madonna and often St Anne surrounded by the infant Christ and Saint John the Baptist – some famous examples of which can be seen above.

Many kind regards

H

Yes, always more than meets the eye. There is a lot of detail and iconography that I miss.

I always learn something new when talking with you.

I love the landscape example you included with the dolomiti in the background. I love this period of art – and learned much from this post! Thanks!

I went back to college I would study history and art. As a teenager I just didn’t appreciate everything these two subjects. Thanks for starting the learning!

🙂 With your love of Europe, it would be a great fit. I loved, loved, loved majoring in art history.

Some really great tips Jenna.

I found the clothing and backdrops especially informative – I found it to be an interesting fact that Botticelli often used Florentine/Tuscan flowers in his paintings – especially in his Primavera painting.

Murissa

Great round-up, thanks for the tour. I think one of the things I like the most about renaissance art is the hidden political innuendos. I always find them humorous and very well hidden. It’s like trying to find Where’s Waldo. I know, it’s silly but I’m a history buff and it’s a fun game I play with myself when I’m looking at art from this period (and others).

I’m always fascinated by the intricate hairstyles that were painted. I know a stylist did a paper/poster on ancient Roman styles (they weren’t wigs!), I bet Botticelli’s would be just as interesting to try to replicate.

Awesome post. I took a couple semesters of art history in college, so this brought me back there. 🙂 Here is something you may not know…did you know that during WWII Hitler was a huge art fan and was salivating at the prospect of taking over/looting the Louvre. The Parisians knew that the invasion was inevitable and had about a 12 day head-start. Leaders put together a team to empty the Louvre and hide ever single piece of artwork/sculpture throughout the city. If you’ve ever been to the Louvre, you know what a monumental task this must have been. I actually saw footage in one of my art history classes of German soldiers going through the Louvre with a look of disbelieve on their faces as not even a frame hung on the walls.

Yes, there are some great documentaries about the Nazis and art all over Europe. There was one that was particularly good, but the name escapes me at the moment.

Did you know that in the Creation of Adam, Michelangelo hid a young African slave in the shadows among the cherubs? His face, in profile, is right there just above the bulge of the uppermost muscle in God’s left arm. Check it out. He’s there, faint as ever, but he’s there. And if you do some digital enhancement on a good high res image you will find his name, also. It was Ali. And more: he writes there that Ali was African, a slave (schiavo), and that he was very fond of him – to be precise, he says ‘Ali, io ti amo’. He used him as a model for one of the ignudi on the same ceiling – the sketch has Ali’s name on it, less well hidden, and he changed the lad’s skin colour, and his face. There are no overtly African Ignudi, but the pose is so exceptional it cannot be mistaken for anyone else, and in the sketch his face is clearly African. And he sketched the same boy some years before, along with some designs for Julius II’s tomb, again with his name, even more prominently when you know where to look. And Ali appears in many other drawings and sketches of the time by other artists, but the reason for this is far more remarkable than his presence in God’s cloud. I’ve tracked him from his birth in 1492 to his death in 1558, and his is one of the most extraordinary stories of the Renaissance. If anyone is interested, let me know and I’ll send some of the visuals, and tell you where else to look to find him (and his two sons, and two of his grandsons!).

Thank you for sharing this–it’s the first time I’ve heard it.

This is a wonderful guide, Jenna! So many things I never would have noticed, like the out of place clothing styles in that biblical work, and also the greater detail that came out in the later part of the period. Also, I’m not sure I’ve ever seen a photo of the Dolomites–how amazing!

So glad you found it helpful, Cassie!

Jenna, by any chance, have you come across paintings of a group of people or angels with faces that look similar? If you have, I would really appreciate the tip. I came across one a few weeks ago but did not write down the artist’s name. Thank you very much.

Hi Alena,

Unfortunately, I can’t guess what that painting could be. If you contact the museum where you saw it, I’m sure they could let you know.